Welcome to another edition of Monday Mapping!

I read something recently (I thought it was from Tor.com but I couldn’t find it there) about fantasy maps in novels. It was particularly critical of fantasy maps as artefacts. By “artefacts” the article meant “fantasy maps in novels that are from the culture and world the book is set in.”

That’s quite different to the standard novel fantasy map. You know the ones: Ye Olde Text, pointy witches’ hat mountains, not much real detail and lots of corny placenames. (If you want an example, google ‘Shannara four lands map’.) This sort of fantasy map is designed for the reader, not for the characters. It serves two purposes: 1) to allow you to track the action, and 2) to immerse you in the feel of the novel. In cartography theory-speak, purpose 1 is the content of the map, and purpose 2 is the form.

A map as artefact, however, purports to be drawn by someone from that world. Ideally it is one that comes to the protagonist’s hand. The ‘not Tor.com’ article suggested these should be avoided because historical maps look nothing like Ye Olde fantasy maps. Historical maps are very hard to read (thwarting purpose 1) and don’t reproduce well in a paperback (obscuring purpose 2). These are good points.

But the way around this problem is to design a secondary fantasy world where it is eminently reasonable for its cartographers to make legible maps at a paperback scale. The map then becomes a cornerstone of the worldbuilding, and its form and content help fulfil both purposes. By inventing a world that does not have to adhere to the dictates of historical cartography, the writer can use map artefacts to inform, mislead, deceive, or do whatever they like.

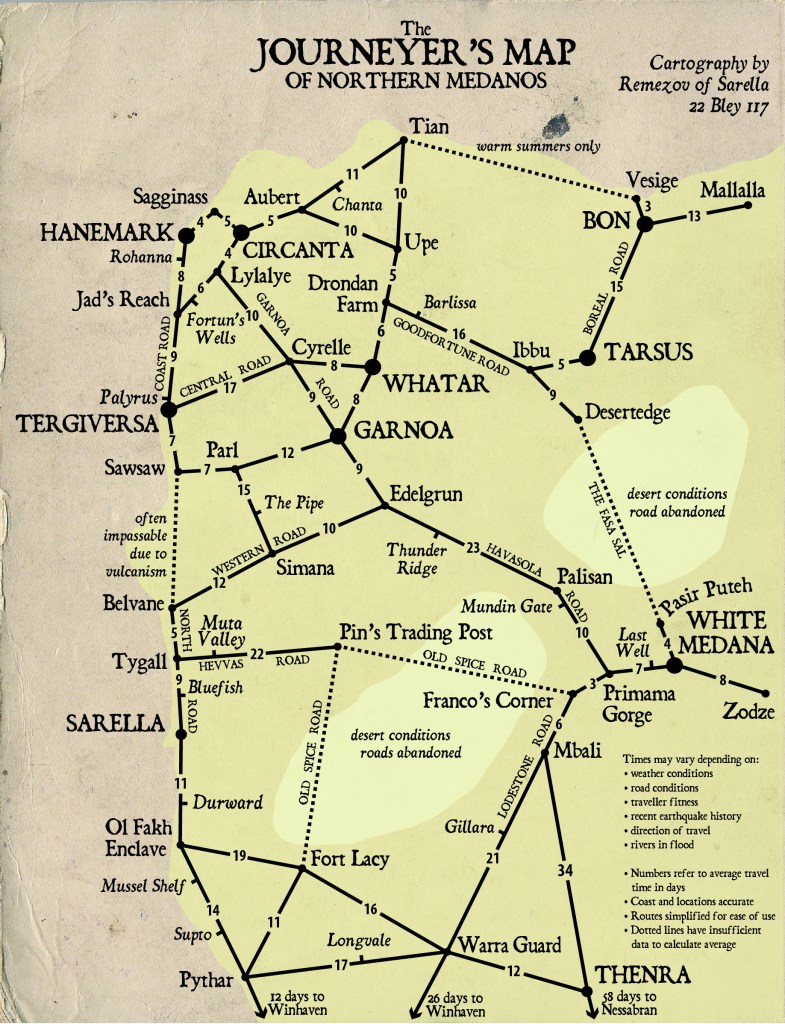

My latest series, The Book of Remezov (the first of which, Silent Sorrow, will be published by IFWG next year), contains twenty such map and map-related artefacts. The novel is set in a secondary world of extreme geological instability, which means geographers and cartographers are in constant demand for their skills and treated like rock stars. Stripped of their certainty, maps are drawn more tentatively than in earthbound cartography. Their content is also wildly different to the physical-based maps of our world.

The map accompanying this article is one example. Its clean style is a result of its maker’s personality – the titular Remezov, a young, arrogant and progressive scientific snob. Not for him the florid maps of the ornamentalists. Make things clean and clear. If the map is about travel times between towns, why even bother going through the drawn-out task of putting physical features on the map? They’re just going to change over time anyway.

Note that many of the artefacts in this novel are drawn by other cartographers, who have their own individual styles and are also influenced by the cartographic movement they subscribe to. Remezov is a constructionist. Along with pragmatists and modernists, he is part of a fresh scientific movement blowing away traditional cartography.

Science is relatively new in this world, and young Remezov one of its leading proponents. He hasn’t yet realised he could improve this map by drawing the length of each line to a time-distance scale. That’ll come, don’t be too hard on the lad.

It’s a true working document, smudged and tatty. Remezov put it together on the three-year journey all apprentice geographers have to make in order to become masters. He’s not afraid to show areas of insufficient information, either.

Each artefact not only illustrates part of the novel, it also contains information and clues useful in understanding what’s going on. I intend readers to view them as part of the text. It’s an experiment. It will be interesting to see how it all works out!

Leave a comment