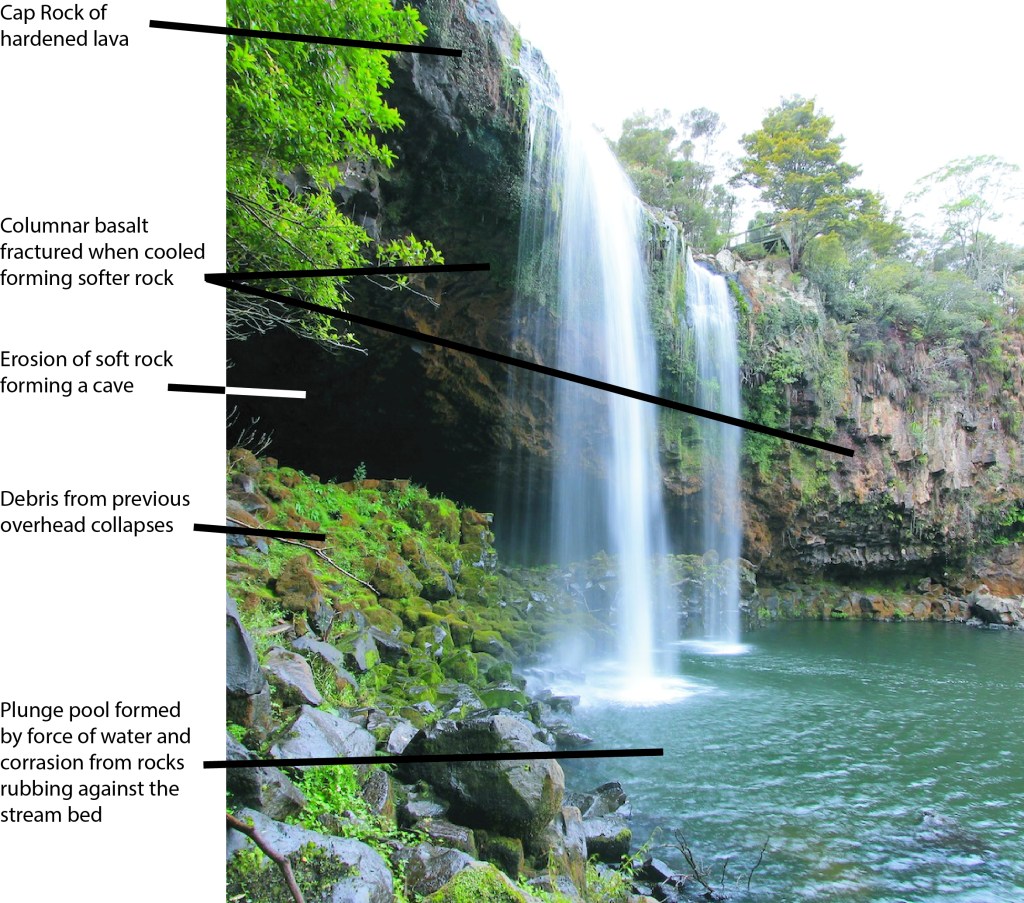

Though waterfalls appear to be permanent parts of the landscape, they are in fact ever-changing and ultimately short-lived features, constantly engineering their own demise. Waterfalls are formed when streams encounter a section of resistant rock (cap rock), while downstream, in softer rock, the stream is deepened more easily. A rapid or waterfall will form at the divide between the harder and softer rocks, and will immediately begin working upstream, undercutting the cap rock to cause overhangs and eventual collapse in a process known as headward erosion.

Downstream of the waterfall a plunge pool forms, eroded by the force of the waterfall and by rocks tumbling under the water, a process called corrasion. As the waterfall progresses upstream it leaves behind a lengthening steep-sided gorge. When the waterfall reaches the upstream end of the hard cap rock its geologically brief life is over, as the whole channel will cut down quickly through the softer rock.

A waterfall’s life-span, therefore, is determined largely by how much water flows down the stream and how hard and extensive the cap rock is.

Rainbow Falls, a lovely fall near Kerikeri in Northland, New Zealand, is a living example of this process. (I visited it many times during the two years I lived in Kerikeri, though we had our own waterfall on our property.) The annotated photograph illustrates erosion in action.

This material is adapted from Russell Kirkpatrick’s 2011 book, Walks to Waterfalls (David Bateman Ltd.).

Leave a comment