Next in my series of cartographic alternatives to standard maps, with their deeply encoded messages, is the schematic map.

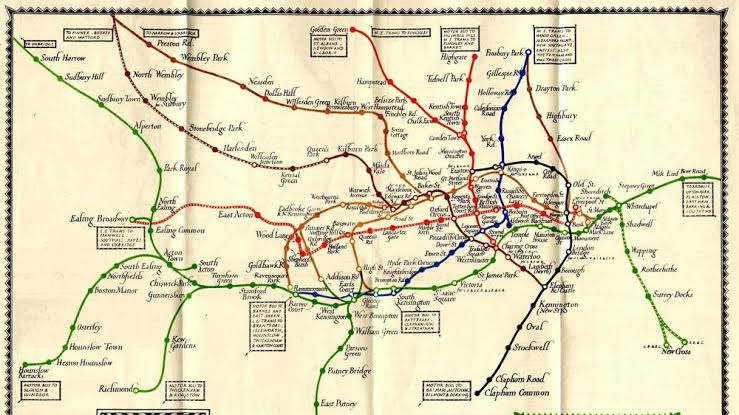

Probably the most well-known example of a schematic map is the Tube Map, the map of the London Underground. Developed in 1931 by Harry Beck, this map simplifies a horrendously complicated three-dimensional railway network to a series of lines and connections. Figure 1 shows pre-1931 maps of the underground, while Figure 2 is Beck’s effort.

The map works because it ignores geography. Who cares about absolute distance and direction? All you want when you take the tube is the connections. Where do I get on? Where do I change trains? Where do I get off? And because I’m underground, the geography doesn’t matter anyway.

Traditional cartographers almost never think of using this technique, because they are deeply ingrained with the falsehood that physical reality is the ‘real’ reality. Harry Beck had no such falsehood clouding his brain, because he wasn’t a cartographer at all: he was an electrical engineer. What you’re looking at, people, is a wiring diagram.

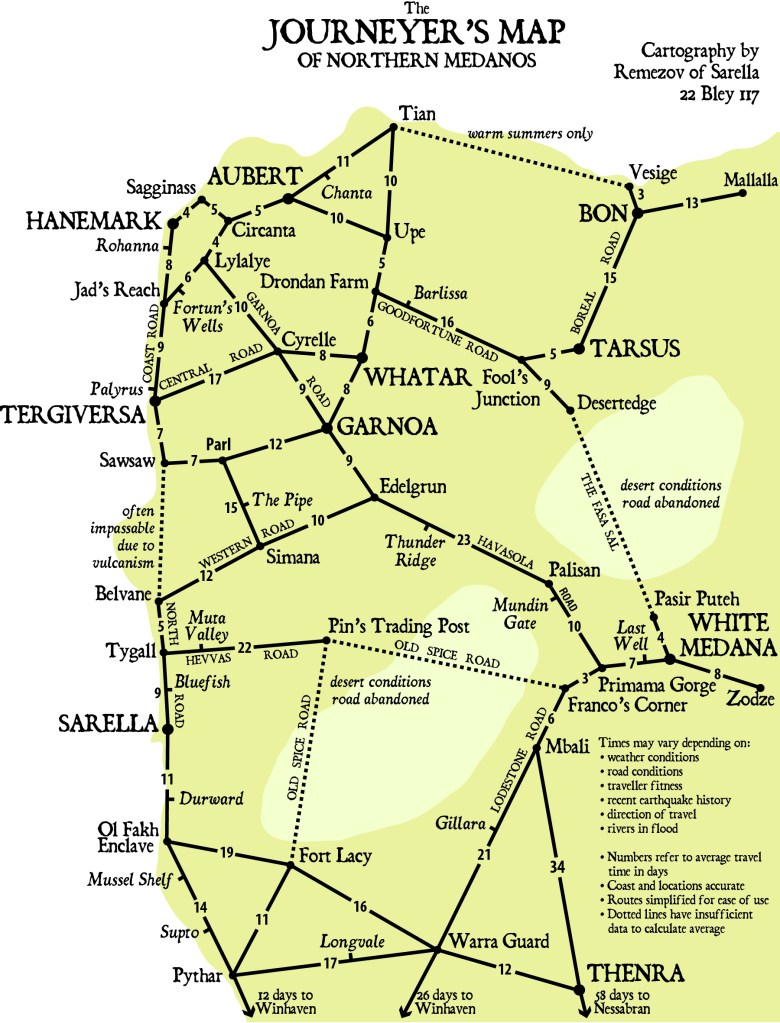

I’ve already shown you one example of this technique in my upcoming fantasy novel, Silent Sorrow; but, now I’ve named and explained it, here it is again (Figure 3). It is a schematic showing time-distance between major centres in northern Medanos, designed by Remezov (the protagonist) to help choose the best routes – because how long it takes to travel somewhere is more important (and often different) than how far it is.

A better cartographer than Remezov (and one of his friends is better, not that he knows this yet) will improve this map further by making the length of the lines proportional to the number of days’ travel the line represents. Who this cartographer is, and how talented she is, will shock him. Good. He needs shocking.

So, logarithmic projections and schematic maps are two viable alternatives to standard cartography. Next week: oblique perspectives.

Really interesting. Looking forward to next post

LikeLike